- Home

- Sydney Alexander

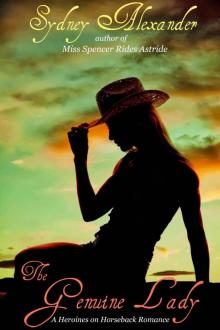

The Genuine Lady (Heroines on Horseback)

The Genuine Lady (Heroines on Horseback) Read online

CONTENTS

Title Page

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

The Genuine Lady

A Heroines on Horseback Novel

Sydney Alexander

Copyright © 2013 Sydney Alexander

All rights reserved.

CHAPTER ONE

This is never going to work.

The hand-mirror told her that she’d overdone it in the sun again. Of course she had; there was work to be done! But here was the damage: her once-pale skin was glowing the color of a ripe tomato, and her cheeks felt as if they were linen pulled tightly across an embroidery hoop. She touched her sore skin with a trembling finger, sighed, and let the little hand-mirror drop to the rough planks of the big work-table. It dominated the room, that table, reminding her that her little world, insecure and shabby as it was, was no larger than a horse’s box in her father’s stables.

What had been her father’s stables.

This is never going to work.

The claim shanty rattled around her, shaking in a sudden burst of hot prairie wind. Oh, that constant wind! The never-ending gusts came panting across the gleaming green grasslands all the way from the Continental Divide. Oh, that interminable wind! She thought she’d never get used to that hateful wind, or, even worse, the stifling pauses between its breaths, when it seemed there wasn’t any air to draw into her lungs at all, nothing but the baking stillness, the inside of an oven. She stopped feeling like an over-stretched piece of linen and re-imagined herself as a flattening, crisping cookie, blackening at the edges.

This dreadful life.

She thought about bursting into tears. But no — that had never been her way. She wouldn’t have come this far if she cried over every glass of milk she had spilt.

And yet still, that persistent voice in her head:

This is never going to work.

She heard a little cry behind her and turned quickly, faded calico swirling with her motion. She was still as graceful as a dancer. Hard work had not tightened her muscles. She peered into the mahogany bassinet and breathed a sigh of relief. He was still quite asleep, the little darling, fast asleep, and only the sighing, creaking groans of the shanty had caused him to stir, clenching his little fists, before he fell back into dreams. She watched him for a few moments, forgetting the taut burning of her cheeks and forehead, the sticky sweat beneath her arms and her breasts and between her legs, and concentrated only on that rosebud mouth, those peach-and-cream cheeks, those few golden curls wisping on his pale forehead.

She almost wished he had awakened, if only to keep her company. Her arms fairly ached with the desire to pick him up and clutch him to her chest, but cuddling would have to wait for the coolness of night. He would never be able to sleep pressed against her heat, and at any rate there was work to be done while the baby napped: wasn’t there always? The next day’s loaf to be set, nappies to be washed and hung in the lee of the shanty, out of the wind so they would not blow across the prairie and disappear, the continued experiment in agricultural construction that was her attempt at a chicken coop… the chores ticked themselves over, one by one, in the back of her brain, and interrupted her adoration of her son. As they always did.

But he was worth it. For him, she would make this dreadful life into something as beautiful as her old one had once been.

***

“There’s a new claim to the north of mine,” Jared said thoughtfully, admiring the amber depths of his cloudy glass. He could still see the bartender’s fingerprints around the rim. The Professor was not an overly fastidious fellow, but a man drank where a man could drink. “Surprised to see someone try to take it on. That’s a rough piece of land.”

“Not much water on it,” his neighbor at the bar agreed, scraping at his black whiskers. “Just that shallow little creek cutting across the southeast corner. Guess a fella could get some water off it though.”

“My creek,” Jared clarified. “The headwaters are from that spring right near my cabin. I’m going to irrigate my wheat fields from that creek.”

“Don’t imagine there’ll be much left for the other claim if you start diverting water.”

“Not my problem, Matt,” Jared said flatly, and tossed back the whiskey with a practiced flick of the wrist. He didn’t even blink at the burn; in fact, sometimes he kinda missed it, that the raw pain that made a boy’s eyes tear up. A man got used to everything, and then he forgot why he’d liked it to begin with. “Can’t help these damn greenhorns, just gotta let them fail on their own and get back on the train East.”

“You were a greenhorn from back East once,” Matt said daringly. “I reckon you were just as foolish.”

Jared glowered down at the dregs in his glass. It wobbled unevenly on the rough splinters of the bar. Last week Tiny Pete had flung Big Pete right through the bar here and it had been hastily patched together with some bits of raw board from Morrison’s lumber-yard. Big Pete was still in his bed at the Red Rose Rooming House, being tended to hand and foot by Miss Rose herself, if rumor was to believed. So it had worked out okay for Big Pete in the end, gossips agreed. Miss Rose wasn’t young, but she had a sweet way about her, and curves like a Kentucky-bred filly.

Jared didn’t see what all the fuss was about, mind you. Miss Rose was long in the tooth and light with her skirt. And Jared had had quite enough of light-skirted ladies pretending to be respectable.

He took off his wide-brimmed cowboy hat and rubbed at his dark-brown hair. He thought maybe he was losing some of it. He’d thought that for years and because of that fear it was too long, falling in loose curls over his ears and his shirt collar and into his eyes, a mop of hair worthy of a some East Coast Dandy, but Jared wasn’t no dandy. He might have been born back East, but he’d been raised on a horse, he’d been roping steers since he was seven, and for Matt to compare him to some tenderfoot from the city was just plain crazy talk.

“I wasn’t never green,” Jared growled finally, liquor rasping at the edges of his deep voice. “I was just young.”

“Sure,” Matt allowed agreeably. Matt was agreeable. That was his strongest talent, his agreeableness. He was the opposite of Jared in that respect. “You was just young. And,” he added slyly, “you never made no mistakes.”

“I made a few,” Jared blurted tensely, more to the bar than to his drinking buddy. “I made a few.” He pushed back his chair suddenly and stood from the bar. The Professor looked up from behind the bar, alert as always to any loud noises that might signal a bar fight was about to commence. He loved a good bet as much as the next man. He saw it was only Jared and shook his head, going back to rubbing glasses with a greasy cloth. Jared never caused trouble. He mighta been a cowboy o

nce, but even then he’d never been the hootin’ hollerin’ hell-raisin’ kind. Jared was a more thoughtful sort of man. He’d talk to a man and take him outside before he’d throw a punch.

“You leavin’?” Matt was still slumped over his glass. He peered up at Jared blearily. “Where you goin’?”

Jared sloped out of the saloon without a word to Matt, and so Matt, used to his old friend’s changeable temper, did not bother to follow him. It was a hot son-of-a-bitch of a day anyway, and not even the bonds of friendship could withstand the pleasure of sitting in a cool dark room and letting another man refill his glass with rotgut, again and again, waiting for night to fall so that he could commence with his inevitable bad behavior and obscure, half-forgotten endings.

And he didn’t need Jared for that. Jared rarely had anything to do with these foolish nights on the town, such as it was, unless he showed up to pick Matt up and brush him off and send him home. He was a good fellow for riding with, a good hand with a horse and a good partner with a rope and a cow, and he had done a dang fine job on his nights with the cook-pot too, but ever since that last winter in Galveston, Jared had got downright sullen. He’d given up the drives and put in a claim and built that cabin along that cold little no-name creek, but still, his mood had gone from bad to worse. Why, Matt could hardly tell if they were even friends anymore, half the time. It was obvious living in one place wasn’t doing him any favors. But when Matt had suggested they join old Captain Jarvis’s cattle drive and spend the coming winter in Galveston, Jared had flared up and told him not to talk nonsense. He was a homesteader now, and he wasn’t goin’ nowhere.

Matt lifted an eyebrow at his empty glass, regarding it sadly, and the Professor took the hint, lifting a bottle with his liver-spotted hand and dropping a few fingers tremblingly into the smudged glass. Matt smiled. The Professor smiled. He wiped a filthy glass on his spotless black vest, splashed it full again, and the two men threw back their portions together. When the Professor raised the bottle again, his hand wasn’t shaking anymore.

Matt knew whiskey was the best medicine, and this just proved it.

***

If this was what a land agent called a creek, then she’d hate to see what he called a puddle. The Atlantic Ocean, most likely.

Cherry surveyed the slow trickle of water without pleasure. To be sure, it was already high summer and she had been assured, by men who were purported by real estate authorities to know these sorts of things, that the water levels would rise with the fall rains, and again with the spring snowmelt. Mr. Henderson at the land office in Chicago had been most confident, hooking his thumbs through his suspenders in a way that belied he was ignorant of any social mores against receiving a lady in his shirtsleeves, and smiling toothily as he assured her that the wandering blue line drawn upon the surveyor’s map would prove to be a rushing torrent of fresh water nine months out of twelve. She would drink, her cattle would drink, her crops would drink: they’d all be giddy with water, essentially.

Looking at it now, though, this muddy orange puddle that was her sole source of water for drinking and bathing, as well as the irrigation for her eventual fields of rippling wheat and her eventual herds of lowing cattle, she could not help but think with stinging regret of the water-meadows of home, the white-faced cattle knee-deep in clear waters sparkling beneath the gentle English sun, surrounded by the lush green hills and shaded by fluffy white tufts of clouds. The sky here was flat, empty, blue at the top but yellowish at the edges, nearly opaque with heat and humidity. The Dakota territory could not be less like the comforts of her homeland. The once-vivid imagery of grains and beasts growing fat and plump in a new garden of Eden were slipping from her mind’s eye; she could not recall her own dreams anymore.

“Stop this, Cherry,” she said aloud, her voice a thin piping against the vast empty prairie. She had taken to talking to herself of late. There were so few other people to talk to. “There’s no use pining for the past. There is only planning for the future.”

They were her father’s words, but she had not her father’s strong voice to speak them in, and for a moment she felt even worse, stranded alone in a strange wilderness she was in no way qualified to stand against. And not truly alone, but the mother of a little son!

Her son. Cherry squared her shoulders and lifted her chin to the horizon. Thoughts of her boy always buoyed her determination to make good on her promises. She would rise to the occasion for him, if not for herself. Lady Charlotte Elizabeth Beacham, only daughter of the late Lord Marcus Beacham, Marquess of Beechfields, dared the prairie to come and devour her. Her papa might never have foreseen his golden princess out here in the American wilderness, but he had raised her to be strong and take on every challenge with grace and honor.

As she had done before, she thought, despite those at home who would have called her disgraced, dishonored. She had done what she had to do.

The society of her birth might consider her honor lost forever, but Cherry knew the haughty aristocrats of the ton were wrong. Sweet Little Edward was no stain upon her honor, no matter what society said. He was a gift, a rare jewel, a precious reminder of love lost, and she would regret nothing — nothing! — in her fight to give him a life and an inheritance as he deserved. The once-Lady Charlotte Beacham, now just Cherry, turned her back on her muddy crick and went back to the waiting mule, ready to send home the quiet little Jorgenson girl and see about supper.

***

The Jorgenson girl went home with a head-bob and a few unintelligible words of Swedish, delivered politely enough, and it wasn’t until her blonde braids had disappeared over the first imperceptible rise to the east that Cherry noticed the little tin of cookies, placed circumspectly in the sparsely populated larder. She pulled out the tin, cheap dented metal decorated with a pattern of pears and apples, the bittersweet reminder of both a beloved, more verdant homeland and the dimming hopes of new Eden, and plucked up the lid with blackened fingernails.

“Butter cookies,” Cherry sighed at the contents, crumbling and yellow and utterly enticing. “That sweet girl.” Cherry’s fledgling homestead as yet had no cow and so, no butter. She imagined that she would have to get a cow soon, and hire someone to teach her how to feed it and milk it and make butter and cheese. The Jorgenson girl would be ideal for a dairy-maid tutor, of course. The lack of a common tongue would make lessons hard, but spreading gossip about the know-nothing Englishwoman even harder. Cherry was sick to death of gossip. It had hounded her from England, and then from New York, and she had no intention of letting whispers and titters ruin her new life in the great sprawl of the American West.

There was a coo from behind her and she turned, setting down the cookie tin at once. “Edward darling!” she whispered. “Are you awake?”

The little boy stirred in his fine crib, one of Cherry’s few relics of her past life, and lifted his tiny hands. He cooed again. Edward was a sweet-tempered boy, more likely to ask for attention than to demand it like most babies.

“Let us sit together,” Cherry suggested to him, and she scooped the baby up and settled down into her rocking chair. The fading gilt scrollwork matched the arabesques and curls carved into the crib. There had been more to the nursery furniture set once; but Cherry would never have been able to carry all that fine old carpentry across an ocean and a continent. She had taken the few pieces she could afford to ship to New York, and raising Little Edward — she had felt certain, from the first quickening, that she carried a son for her lost love, and named him before he was born — in the Beechfields crib, and rocking him in the Beechfields rocking chair, had seemed indispensable.

She nuzzled the baby and smiled. “I feel certain you would like your tea,” she told him. She had grown used to speaking to the babe as she would another adult in the room. Living without company could do that to a woman, she supposed, but if she didn’t speak to Little Edward, who would? They were alone out here on the prairie, like castaways at sea.

She had seen such a differen

t future for herself once, one with a husband who adored her, and children all around them. But she had been a different person then, with a different life, and a different name. Now there was only Little Edward. But she adored him; he was enough.

Cherry unbuttoned the blouse of her faded dress and let Edward make himself comfortable. Soothed by his suckling, worn out with her day spent in the Dakota sun, whipped by the Dakota wind, she slipped into sleep before the boy did, and as the shadows lengthened the two slumbered luxuriously in the rocking chair, the little boy’s hand splayed open upon his mother’s white-skinned breast.

CHAPTER TWO

Jared thought he was going home. Jared’s horse thought he was going home. They traipsed out of town, Jared’s mind on bitter lost love, the horse’s mind on oats. The horse’s thoughts were more urgent than Jared’s, and that’s why when Jared reined back at the little cottonwood patch that marked the easterly line of his claim, and sat looking around the empty prairie in an uncharacteristic agony of indecision, the frustrated horse flung his head up and down with exasperation and was rewarded with a heel in the ribs.

“Now you cut that out,” Jared scolded, voice harsh, and the roan horse dipped his freckled head, pretending to be contrite, but really angling his nose towards a lush-looking tuft of summer grass. Jared did not reprimand the horse as he might have usually, but sat gazing up the imaginary line, still studded every so often with the surveyor’s stakes that demarcated his claim from the neighboring one, wondering what sort of greenhorn would have taken on that rough patch of land to his north and east. The roan horse grazed and grazed, contentment in his heart, and Jared puzzled.

It wasn’t just that there wasn’t much water on the land. Only about half the claim was any good at all. The south-half was just fine, sure. But the northern quarter of the tract was all badlands: just rocks and brush and snakes, no good for wheat. He’d ridden the entire section; hell he’d ridden the entire county, looking for the best possible claim to homestead, and this particular piece of land was about the worst bargain in the county.

The Genuine Lady (Heroines on Horseback)

The Genuine Lady (Heroines on Horseback)